The Emperor’s True Face: Realism and Image in Ancient Coin Portraiture

Denis Richard, Coin Photography Studio

May 24, 2025

🕒 8-minute read

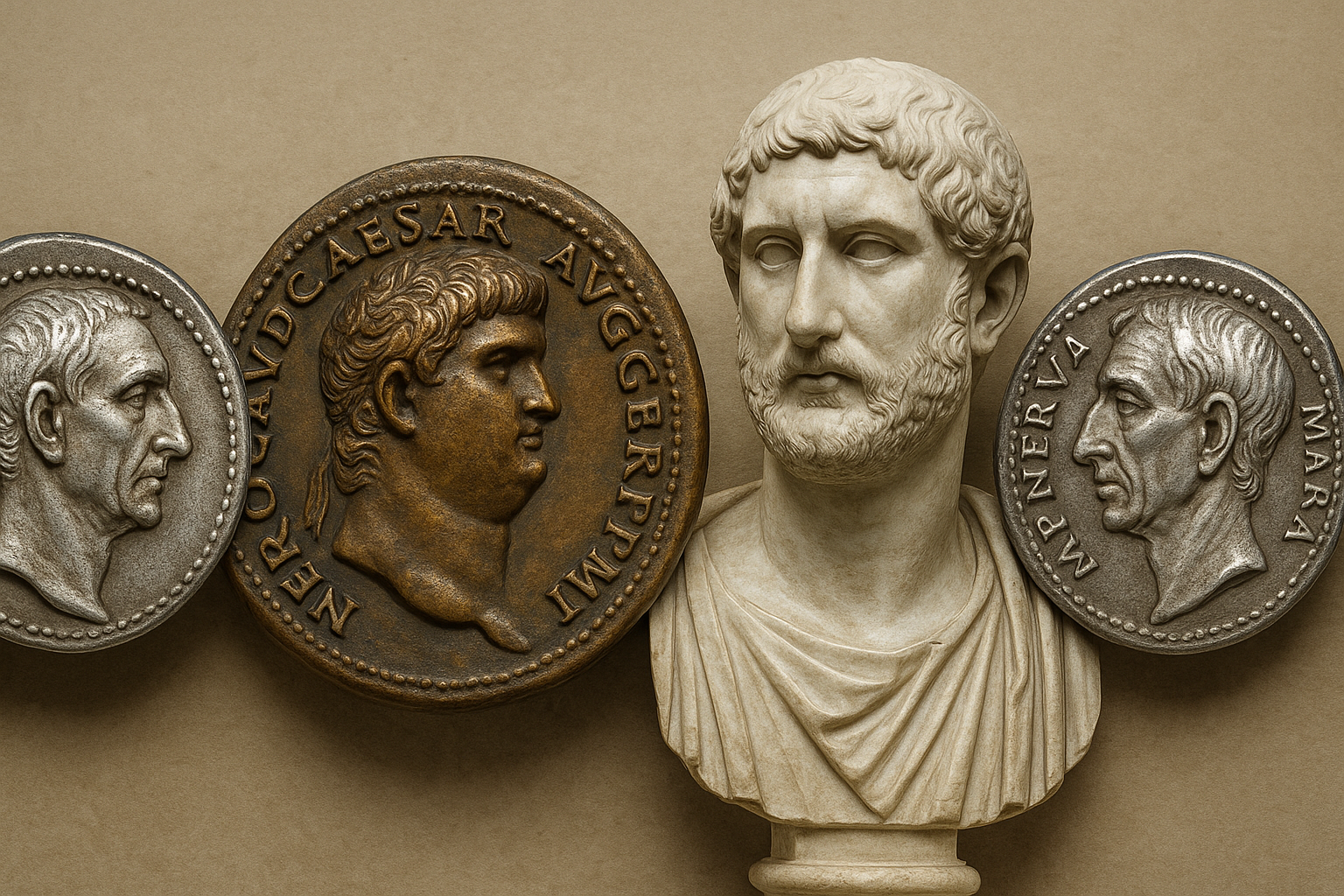

An AI-generated composition highlighting the contrast between realistic, often unflattering, coin portraits of Roman emperors and their idealized marble busts.

Why did Rome, a civilization capable of sculpting divine perfection in marble, so often choose to immortalize its emperors with such raw, even unflatteringly realistic portraits stamped into Roman coins by the millions? What message did those wrinkles carry? This is the story of verism—a uniquely Roman aesthetic that turned age into authority and made coinage a canvas for truth, propaganda, and political survival.

Verism in Roman art is the practice of depicting subjects realistically, even unflatteringly. If you've ever examined ancient Roman coin portraits, they depict many emperors with every wrinkle, crease, and imperfect feature visible. These realistic coin portraits contrast the idealized images we often see in marble statues. Why would Romans portray their leaders as "warts and all"? The answer lies in Roman values and the role of ancient Roman coinage in spreading imperial imagery. In this post, we'll explore how verism reflected traits like gravitas (seriousness) and virtue (virtue), using examples of Julius Caesar, Nero, Hadrian, and Nerva. We'll also compare their coin portraits with marble busts to see how coins sometimes presented a more unvarnished truth than statues.

What Is Verism in Roman Art?

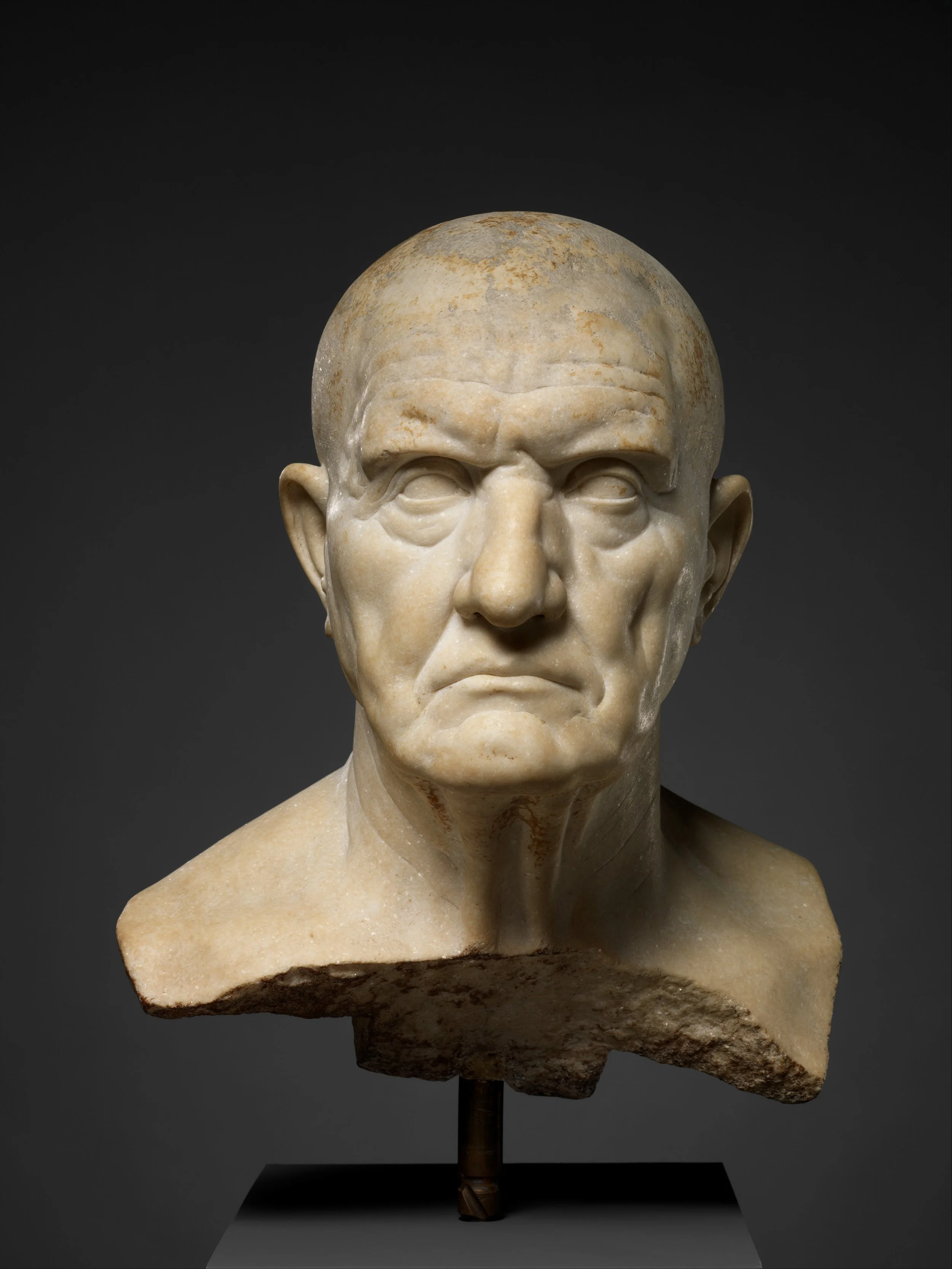

Bust of A Man, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Verism (from Latin verus, "true") refers to a highly realistic style in Roman art. During the late Republic, Roman aristocrats favoured portraits highlighting signs of age and experience—every wrinkle, furrow, and line was a badge of honour. Rather than smoothing over imperfections, veristic portraits emphasized them. This style was prevalent in Republican portrait busts of elders, where a lined, weathered face conveyed wisdom, courage, and service to the state. In a culture that venerated the Mos Maiorum (ancestral tradition), showing a wrinkled, aged face signified gravitas and a life of duty.

When the Roman Empire began, portrait styles cycled between "veristic" realism and classicizing idealism depending on the message each emperor wanted to send. Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (like Augustus) often chose youthful, idealized depictions to stress continuity with a golden age. But others, especially after periods of turmoil, reverted to verism to project a sense of traditional, no-nonsense leadership. Coins, being mass-produced official images of the emperor, provide some of the best evidence of these stylistic choices.

Roman Coins vs. Marble Busts: Idealization and Reality

It's important to remember that Roman emperors' images appeared in many forms – from marble statues in forums to painted portraits and coins circulating throughout the empire. Marble busts displayed in public spaces could sometimes be idealized or even re-cut to resemble new rulers. Coins, however, were issued regularly and needed to be recognizable. This gave coin engravers an incentive to emphasize distinctive facial features. In some cases, coin portraits might have been more up-to-date and candid than sculptures, which could be expensive and time-consuming to replace.

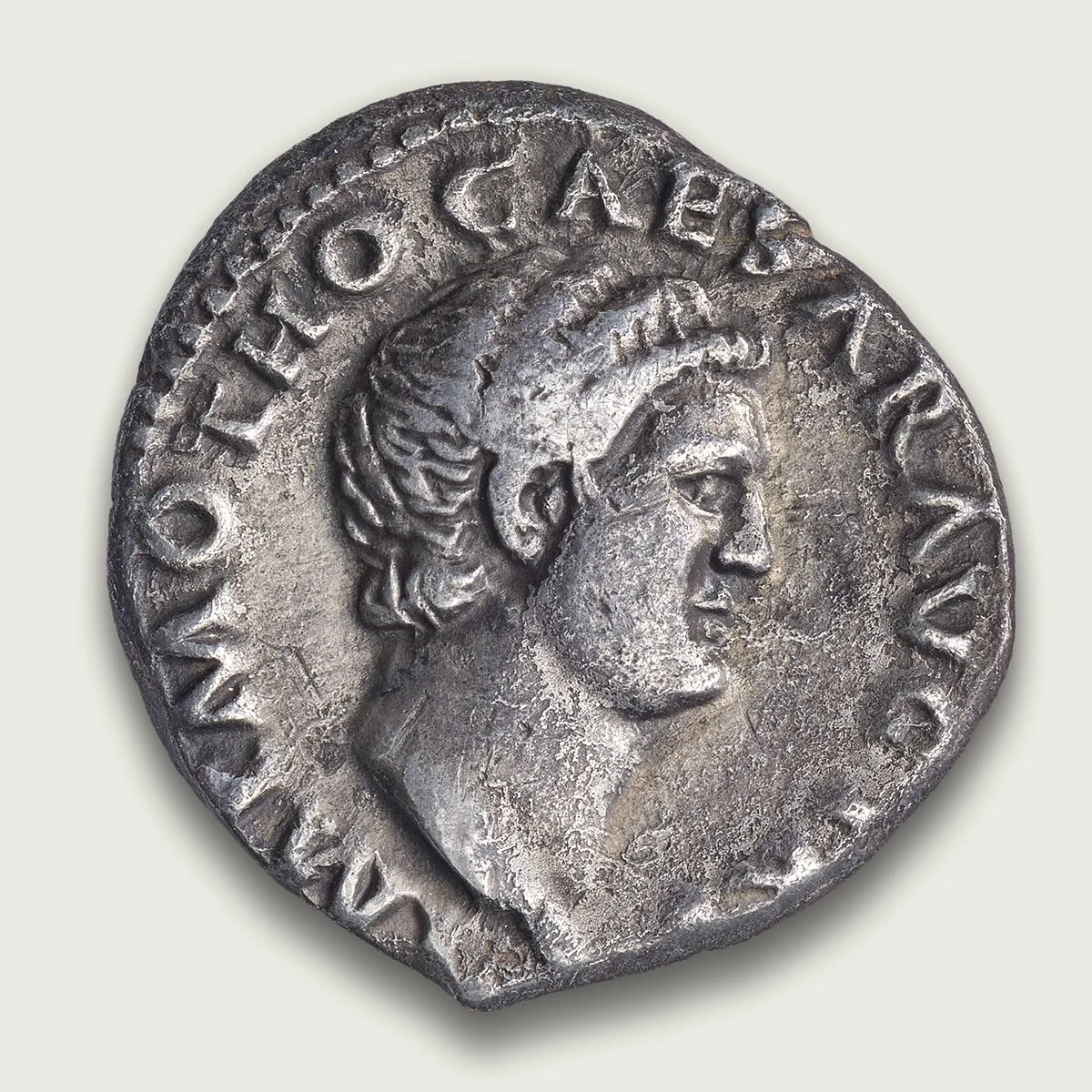

Roman Emperor Otho, Silver Denarius, 69 CE

The historian Suetonius notes that Emperor Otho, a former companion of Nero, styled his hair on his coins to imitate Nero's look. With coinage, any message could be recorded and disseminated quickly. On average, Emperors or Empresses produced 38 coin types during their reign. Meanwhile, outlying provinces’ statues might still have an idealized image decades later.

When we compare Roman coins vs. statues, we often find that coins provide a more unvarnished look at the emperor's appearance and how he wanted to be perceived at that time.

Below, we'll examine four emperors – Julius Caesar, Nero, Hadrian, and Nerva – to see how their coin portraits compared with their marble busts and what these images communicate.

Julius Caesar: The First Living Portrait on a Coin

Julius Caesar, Silver Denarius, 44 BCE

Julius Caesar's coin portrait – struck by moneyer Marcus Mettius – broke with tradition as he became the first living Roman to put his face on the coinage. This denarius shows Caesar with a lined face: a wrinkled neck, sunken cheeks, and receding hair under his laurel wreath. Far from flattery, the image emphasizes his age and gravitas. In fact, Caesar was likely in his mid-50s, but the engravers exaggerated his wrinkles to align with Republican portrait norms that honoured age and experience. This coin proclaimed his unprecedented power while the realism of his portrait tried to frame him as a traditional, elder statesman.

Marble bust of Julius Caesar (Tusculum portrait, c. 50–40 BC, Turin)

This bust – believed to be a lifetime portrait – shows the same features on the coin. His brow is deeply lined, and his neck is creased with wrinkles. Notably, later posthumous busts of Caesar often smoothed out these flaws, portraying him in a more idealized manner. But the Tusculum bust and the coins struck by moneyer Marcus Mettius share a truthful quality: Caesar appears as a balding, older man hardened by years of campaign. According to scholars, the coin and bust's unflattering realism (verism) marked Caesar as a battle-worn general of the Republic rather than a youthful Hellenistic king. For Romans of the time, this truthful depiction was a statement of Republican virtue – an image of authority earned through wisdom and service, not divine perfection..

Nero: From Youthful Prince to Caricature of Decadence

Nero's reign (AD 54–68) offers a fascinating look at changing portraiture. As a teenager-turned-emperor, Nero's early coin portraits followed the Julio-Claudian template of youthful, smooth features. On those initial coins, he appears almost cherubic and idealized – in line with Augustus's tradition of eternal youth. However, around AD 64, something changed. Numismatic experts note that Nero's coins became much more realistic as he aged, even to the point of exaggeration. His later silver denarii and bronze sestertii show a heavier face with a fleshy neck and a hint of a beard, reflecting Nero's physical growth and self-indulgent lifestyle.

Bronze Sestertius of Nero (c. 54-68 CE)

The coin's obverse shows Nero with a laurel crown, fleshy jowls, and a pronounced curl of hair. By this time, Nero was not the slim youth he once was. The coin engravers did not shy away from depicting his fuller cheeks and thicker neck. Some historians argue that the verisimilitude was the point of Nero's coinage – to show him as he truly was. This was a departure from earlier emperors. The care taken to strike Nero's likeness "warts and all" on coins suggests an official endorsement of realism, perhaps to underscore stability or simply Nero's acceptance of his image.

Marble bust of Nero (Palatine Museum, Rome)

This bust captures Nero in his later years. We see the same heavy-set features: a broad face with small, pursed lips and a distinctive neck-beard creeping along his chin. His hairstyle is intricately carved with the fashionably curly locks he favoured. When we compare the bust to the coin, the likeness is unmistakable. If anything, the bust is slightly more flattering because marble has a way of abstracting blemishes. But overall, Nero's portraiture – both in marble and on coins – became increasingly unidealized as his reign progressed. Some contemporary critics likened his final coin portraits to a "caricature," but they are valuable today for showing us the real face of an emperor famous for his vices. For Romans, depicting Nero's weight and eccentric grooming may have been a way to communicate his evolving identity (he fancied himself an artistic, almost Hellenistic king by the end). Yet it also allowed his successors (the Flavian emperors) to later contrast themselves as simpler, soldierly types with rugged features – a deliberate shift back to Republican-style verism.

It's worth noting that statues of Nero are relatively rare today—not because they were never made, but because many were destroyed. After Nero's suicide in AD 68, the Roman Senate declared a damnatio memoriae against him, a formal condemnation that sought to erase his memory from public life. This meant tearing down statues, chiselling out inscriptions, and even re-carving Nero's likeness into that of later emperors. One notable example is a marble portrait now in the Museo Nazionale delle Terme in Rome, which originally depicted Nero but was later reworked to resemble his successor, Vespasian. Art historians have identified the reuse by analyzing mismatched facial features and tool marks beneath the surface carving. As a result of this campaign, Nero's surviving busts are rare. Many that did exist were literally transformed into someone else. Ironically, his coins—minted in vast quantities and beyond easy recall—survived the purge intact, offering a far more complete visual record of Nero's evolving appearance than the sculptural record does. In that sense, coins provide not just a portrait of Nero but also a historical trace of what official art tried to erase.

Hadrian: The Bearded Philosopher Emperor

Hadrian (reigned AD 117–138) is notable for reintroducing the full beard into imperial imagery. Unlike predecessors who were clean-shaven, Hadrian appeared with a philosopher's beard in all his portraits – coins and statues alike. This was partly a nod to Greek fashion and philosophy (he was a famous Hellenophile), but it also conveniently covered any imperfections. Hadrian may have had some natural blemishes or preferred the beard's mature look.

Silver Denarius of Hadrian

On this coin's obverse, Hadrian's bust is shown laureate and draped, with his curly hair and full beard visible. The realistic coin image faithfully includes Hadrian's distinctive facial hair and adult features, setting him apart from earlier emperors. However, Hadrian's face on coins is often somewhat idealized: generally smooth and calm, without deep wrinkles. An Art Institute analysis of a Hadrian marble head notes "the smooth, unwrinkled appearance of the emperor's broad face," with only subtle lines around the cheeks. This suggests that while Hadrian embraced a real detail (the beard), he didn't go out of his way to appear aged or haggard. Instead, his portraits project a mature but ageless image – a balance between realism and the timeless youth of Augustus's precedent.

Marble bust of Hadrian (Capitoline Museums, Rome)

Hadrian's bust presents him in military dress, eyes gazing slightly upward. His curly hair and beard are meticulously carved, each lock and curl rendered with depth. Yet his face remains relatively unlined, showing perhaps only the faint crease of the nasolabial fold beside the mouth. Hadrian crafted a portrait style conveying wisdom and vitality by combining veristic detail (hair, beard) with an otherwise ideal complexion. He set a trend: the Antonine emperors after him all sported beards and often maintained a similarly moderated realism – they appeared as never-aging, bearded adults in a kind of familial resemblance to Hadrian. In Hadrian's case, coins and busts were remarkably consistent; the coins disseminated his bearded image across the empire, aligning the whole realm with his new look. This is an excellent example of how imperial portraits on coins could usher in a new visual identity for the emperor that statues would then reinforce

Nerva: Age and Wisdom on the Coinage

When Nerva became emperor in AD 96, he was almost 66 years old – essentially a grandfather among emperors. After the bloody end of Domitian's reign, Nerva's rule was meant to be a return to old Roman virtues. His portraits underscored this by unapologetically showing his age. Nerva's coin portraits depict a thin-faced, older man with a sharp nose, crow's feet, and a receding hairline. There was no attempt to mask his wrinkles; in fact, highlighting them helped legitimize Nerva's authority as a wise, experienced leader (despite his short reign).

Silver Denarius of Nerva (AD 97)

The obverse of this coin (left) shows Nerva's head laureate, facing right. Even in the coin's small size, one can make outlines on his neck and a certain gauntness to his cheeks. His nose is prominent and hooked, and the overall impression is of an unpretentious, elderly man. This was quite deliberate. After Domitian, who had styled himself as a perpetually young autocrat, the Senate-backed Nerva needed to appear as the anti-Domitian: a humble, traditional Roman elder. His coin inscriptions tout things like LIBERTAS PVBLICA (public freedom) and AEQVITAS (fairness), aligning with an image of a benign elder restoring liberties. The realistic portrait reinforces the message – Nerva looks like someone who has seen a lifetime of service and can be trusted to govern wisely.

Unknown Portrait of Nerva (30–98 CE)

Now, compare this to Nerva's sculpted likeness in marble. Unfortunately, Nerva's official busts are rare, but one famous example is a portrait in the National Roman Museum of Palazzo Massimo. Busts of Nerva show him with the same thin face and hooked nose. In some busts, the carving of the brow and cheeks is gentle, smoothing his older features. Nonetheless, he is no Adonis: Nerva's statuary keeps his aged appearance intact, emphasizing a sober demeanour. Roman writers like Pliny the Younger praised Nerva for his moderation and wisdom, qualities effectively communicated by his aged visage.

In essence, Nerva's coinage and portraits send a clear message: the emperor is a seasoned statesman chosen to put Rome back on track. The coins' unflattering realism (to our eyes) was likely reassuring to Roman citizens and senators. It signalled a rejection of the vanity and excess that they associated with the previous regime. Here was an emperor who didn't need to appear as a youthful god; rather, his power was grounded in Roman tradition and the collective memory of the Republic's elder senators.

Why "Ugly" Portraits? Roman Values Behind the Images

As we've seen, many Roman coin portraits were not trying to win beauty contests. From Caesar's leathery neck to Nero's double chin, these images often feel strikingly frank. Why did the Romans value this kind of realism?

Firstly, Romans associated physical signs of aging with virtue and authority. In a society that esteemed its elders (the Senate itself means "Council of Elders"), wrinkles were honourable. A lined face implied a life of virtuous effort, military command, and republican simplicity. Showing an emperor in this veristic way linked him to the Republican tradition of venerable leaders. It said: "Despite being an emperor, I am still a civis Romanus of the old school." Coins were the perfect medium to broadcast this message widely, as they reached every corner of the empire in the hands of soldiers, merchants, and citizens.

Secondly, Roman audiences were used to ancestral images – wax death masks of ancestors that were kept and displayed by aristocratic families. These images were very realistic (essentially moulds of the person's face) and often quite grim-looking—veristic portraits tapped into this cultural practice by giving emperors the gravitas of one's revered ancestors. An emperor depicted with the "warts and all" verism signalled continuity with the values of those ancestors.

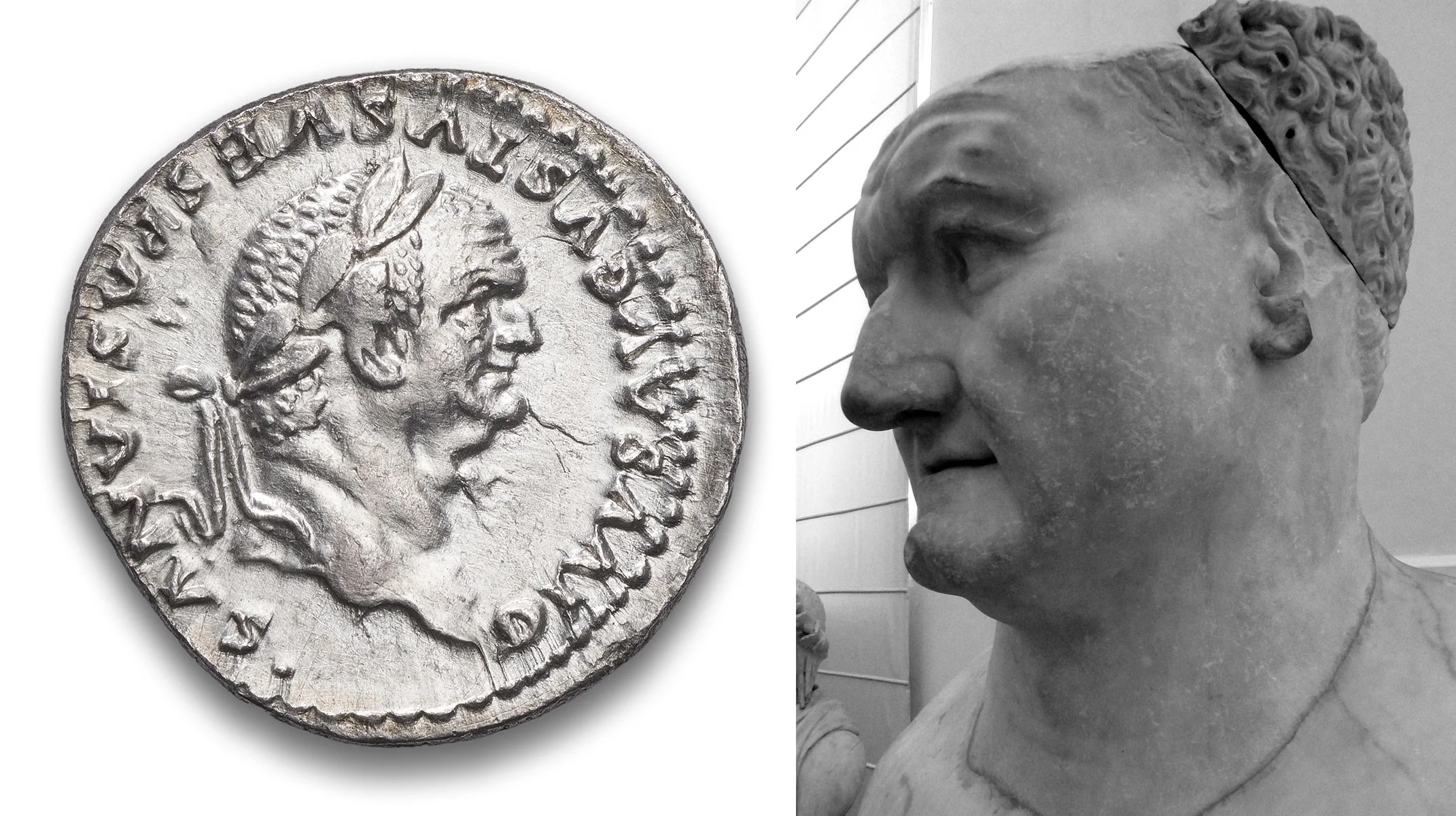

Trajan Silver Denarius, 98-117 CE

Finally, not all emperors opted for verism. The pendulum swung back and forth. Emperors like Trajan (left) and Augustus favoured a more idealized, ageless look to promote a golden age image. Portraits on coins from the beginning of Augustus's reign in 27 BCE look almost identical to those struck right before his death at age 75, 41 years later.

But tellingly, after periods of instability, the successive rulers often embraced realism to differentiate themselves. Vespasian, below, for example, after Nero's extravagance, had a rugged, sun-weathered face on his coins – a deliberate "anti-Nero" statement. In that sense, verism was a political tool. An unflattering coin portrait could be propaganda in its own right, broadcasting honesty, stoicism, and alignment with traditional Roman morals.

Roman coins versus statues also sometimes differed in purpose. A marble statue in the Forum might be designed to emphasize the emperor's godlike qualities or military prowess (through costume, pose, or an idealized face). On the other hand, a coin circulated among everyday people, so portraying a knowable, human likeness of the emperor aided recognition and a sense of personal connection to the ruler. The realism on coins made the emperor real to subjects across vast distances – his face, with all its lines, looked like someone who would appear in person. In a world without mass media, the coin was the emperor's portrait in your hand.

In conclusion, verism in Roman imperial portraiture was far more than an artistic quirk. It was a visual language loaded with meaning. The "unflattering" portraits of emperors on many Roman coins were a feature, not a bug – they reflected and reinforced Roman ideals of virtus, gravitas, and respect for tradition. Whether it's Julius Caesar looking every bit the battle-weary dictator or Nerva presenting himself as the aged saviour of Rome's liberty, these realistic images told ancient viewers that what you saw was what you got. In a way, verism was a form of honesty in advertising.

Silver Denarius of Emperor Vitellius. 69 CE. Vitellius was Roman emperor for eight months, until he was executed in Rome by Vespasian's soldiers on 20 December 69.

For numismatists and history enthusiasts today, these coin portraits are incredibly valuable. By comparing them with marble busts, we gain insight into the messages each emperor wanted to convey. We also see the push and pull between idealism and realism that defined Roman art. Ultimately, those realistic Roman coin portraits – the ones with crow's feet, receding hairlines, and wart-covered profiles – bring us face-to-face with the Romans' nuanced understanding of power and virtue.

Image Credits: All coin photography by Coin Photography Studio. Bust images are courtesy of museum collections and Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

A Final Thought.

Thank you for reading this blog post! I hope you found it informative and enjoyable.

If you're interested in similar topics, be sure to check out our other posts on numismatic subjects. From coin history to coin photography, we have lots to offer.

Remember to leave a comment below with your thoughts and feedback. We love hearing from our readers, and it helps us improve our content.

Thank you again for your support, and we hope to see you back here soon! Happy collecting!